(Also see my follow-up post on getting organized, and sign up to my tiny letter to get contacted about fixing housing affordability in SF).

San Francisco’s housing system is broken. The only way to fix it is through a radical change in our housing policy: a change that encourages (a lot of) building.

Failed public policy and political leadership has resulted in a massive imbalance between how much the city’s population has grown this century versus how much housing has been built. The last thirteen years worth of new housing units built is approximately equal to the population growth of the last two years.[0]

Last Wednesday I moderated a panel where two housing experts made arguments that were surprising in two ways: first in how disconnected they were from the causes of the housing crisis and second in how distant they both were from genuine solutions. This post is my response to their arguments.[1][2]

Simply put, the laws of supply and demand do apply to our housing market and I conclude this post by proposing 10 policy solutions that might actually increase the supply of housing in San Francisco in the face of an unprecedented and largely ignored demand. Some of the ideas are large shifts in public policy, but we’ve waited too long for anything less than bold action to work.

(0) San Francisco is moving toward a dystopian future

If we do not change our current housing strategy, the natural result will be a type of cultural destruction. It's easy to point to individual cases of displacement that pull on the heart-strings — a tech family is throwing out grandma to convert a duplex into a mansion (which is genuinely sad and should be prevented!) — but the real displacement is happening at a macro level. We are on a self-imposed path leading to only one place: a city that is entirely rich and, more or less, entirely white. That isn't the fault of any one person on either side, but it is the fault of those that refuse to allow any rational policy response to people's desire to live here.

In time, housing and everything else will become so expensive that we will price every working- and middle-class person out of the city. The gentrification wave will keep rolling. A bubble might burst here or there, but ultimately San Francisco is so self-destructively finite that all the regular people will be pushed to the East Bay, to Pacifica, to Daly City, etc.

Housing demand will only increase with time. Younger folks, like me, want to live in urban centers, and many don't want cars. Companies are moving back to cities as their workers do. In the technology sector, startups and investors will continue to migrate up to the city, as an ecosystem built around proximity and the sharing of ideas (the things that have always made "Silicon Valley" so successful) is even more compelling with urban density.

(1) My goal for San Francisco is a diverse city

In my first job out of college in 2009 I earned $45,000 a year, more than either of my parents had ever made at the time. To many that would seem like a lot of money for a single guy, but by no means was I affluent. I loved the Brooklyn neighborhood I lived in before moving to San Francisco, on the edge of a few different neighborhoods, right where Windsor Terrace becomes Kensington below Prospect Park.

One of the things, if not the thing, that I loved most about that neighborhood was that it felt like what a diverse urban landscape could and should feel like. Within blocks of my building and inside it, there were Russians, Ukrainians, Poles, yuppie white folks like me, Hasidic Jews, African-American and West African blacks (nearby Flatbush is one of the largest black neighborhoods in New York City), Ecuadorians, West Indians, Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, Pakistanis, and more, with wonderful, family-owned restaurants and shops to match these many micro-communities.

I want to live in a beautiful, multiethnic, socioeconomically mixed community. A city where people of low, moderate, and high incomes live together, and people of different ethnicities interact. That's my dream. That's why I love cities: people mixing together, cross-pollinating perspectives and experiences.

That's not San Francisco right now. It might have been in the past, but it certainly won't be in the future — unless we get over ourselves and start building much more housing. Everywhere. Immediately.

(More public transit, too, but that's another post).

(2) A little self awareness about my my role and position in San Francisco

I am perceived to be part of the problem. I'm aware of that fact. I'm a white, male, Ivy League-educated, startup founder who sold his company to a bank (even if my goal was infrastructure for financial empowerment). My office is in SOMA, and I live in a rent-controlled apartment near Dolores Park in the Mission. I eat at expensive restaurants on Valencia Street and buy my groceries at Bi-Rite or Whole Foods because the marginal cost of food doesn't matter much to me.

But I am also the son of a waitress and a (intermittently unemployed) former postal employee, I participated in the free-lunch program at my public schools, and I grew up in a working-class neighborhood. My interest in public policy stems from a deeply-rooted belief that society is often pretty screwed up, the market often fails, privileges (class, race, gender, and more) alter people’s lives and are not just punch lines, and justice is something to be sought.

I don't want the wonderful city of San Francisco to only house the rich. It doesn't sit right with me. It’s unfair. That’s not the type of city I want to live in.

(3) The cause of our housing problem is huge demand in the face of limited supply

People love living in San Francisco. People want to live here. People like it here. They flock here. They also like to have second homes here. People from all over the world still move to San Francisco for the same good reasons that they have since the city's founding in June 1776: location and industry. The benefits of living in San Francisco are easy to see: fascinating culture and wonderful cultural institutions, a diverse dining scene, a robust economy, immense natural beauty, good weather, and a rich history.

How do we respond to this demand? So far, by putting our heads in the sand. By saying: "No, no, no, no, no. The city should not change. The city cannot change.”

News flash: the city is changing and only for the worse. The city is forcing people out. Only the rich can live here because of the policies created by so-called progressives and so-called housing advocates.

"Preserving neighborhood character" might as well be code for "don't build any affordable housing in the city" and, more bluntly, "don't build any housing that doesn't look like mine or has people living in it who don't look like me". Or, more cynically, “don’t build anything that could possible make my house less valuable.” This city is full of folks who are millionaires by virtue of a house they bought, but they feel middle-class. Amazingly, at the same time, they feel entitled to hold the view that the city needs to be more diverse and inclusionary AND it's everyone's fault but their own.

People like to wrap themselves in the flag of keeping things as they are, but that's the attitude that, when combined with people's desire to live here, is screwing over regular people. To only blame a subsection of the people who want to live here — whether they work in tech or whatever — is to blind oneself to the reality that that is only half the story. The other half of the story is how many people refuse to let anything get built.

Yes, to appropriately respond to demand, many blocks in this city need a high-rise building. We're going to have to deal with that fact if we want to solve the problem, rather than just talk about it.

(4) Incorrect claim 1: There are so many empty units out there that we don’t need to build anything

Some folks claim that we do not have to build a single additional unit of housing to solve the affordability crisis.[3] They say that we could solve the problem only with existing units that are currently vacant (for example, full-time Airbnbs or would-be landlords holding out for higher prices).

Let's pause for a moment and consider how absurd that notion is when subjected to any rational examination. The size of the housing crisis and the degree of excess demand is nearly unfathomably large and, in the face of that, some city residents think nothing has to change in the physical development of the city? That's illogical.

I’ve heard estimates, including from a city planning commissioner, that there are over 10,000 empty units, but I’ve never seen any hard data or firm citations to support this. There are actually more units than that vacant right now. In 2014, the Census Bureau estimated 31,686 vacant units. Roughly 3% of rental units and 0.9% of owned units were empty then, fractions of the national average of 6.9% of rental units (4.6% in California) and 2.1% of owned units nationally (1.6 in California).

Why are these units empty? Because units are sometimes empty! Renters move out, others move in, people do renovations, people are showing the house for sale, etc. We have far fewer vacant units than the national average and a similar amount to other booming tech cities like Austin and Seattle. These units can’t be miracled into the housing supply because they already have been, which is why our vacancy rates are so low.

The people who cite the number of vacant units are often unwilling to accept any increase in density or, it seems, even the notion that building matters. I don't know how to deal with that level of denial: by all objective standards, we don’t have that many vacant units and unit owners have few rational reasons to keep their units empty when prices are so high.

(5) Incorrect claim 2: Investment capital will never build affordable housing

Many in the city spend time railing against the apolitical nature of investment capital and how it doesn't care about people: only the highest possible returns.[4] Focusing on capital easily misrepresents the problems we face in the city, and is an easier punching bag in an era where people are outraged about anything that sounds like finance.[5]

Capital is generally impersonal and seeking returns, no doubt, but capital is actually complicated, multi-faceted and diverse. Capital does not necessarily seek out the highest returns but rather the highest risk-adjusted returns. There are many different capital sources out there, all of whom are seeking different risk and return profiles. There are people who would build lower return, lower risk housing in San Francisco if anything could be built at all.

Capital would invest in San Francisco if we had better housing policies: not necessarily higher returns. Big investors in long-term real estate projects nationally include patient capital, like pensions funds, including CalPERs and CalSTRS, who actually want low-risk, consistent returns. They invest in affordable housing elsewhere. But those types of investments are hard to make in San Francisco because the risks aren’t low and the consistency isn’t there: any investor would be scared by a city currently considering whether to retroactively applying new affordable housing laws.

It’s claimed that the fact that projects that had entitlements in 2008-10 and weren’t built was because capital couldn't get the return they wanted. That's inaccurate. Nothing got built in 2009/10 not because there was no demand or returns in San Francisco it didn't get built because the world was falling apart. It was ultimately a liquidity crisis not a lack of returns.[6] People weren't squabbling about market rent vs. below-market rent, they were worried about whether they were going to be in business the next day.

Further, if we had a process that didn't take so many years, some of the entitled housing in 2008/9 could have gotten built before the financial collapse of the national housing market. Instead, whenever we get to a point in the cycle where there is boom, there is no responsiveness because the process takes so goddamn long. Worse still is when we can harness the market to build, that’s the time when some housing activists stop all building because ... they don't like the profile of the people who want to live in this city.

The reason that only expensive housing gets built is because that's the only housing it makes sense to build in a city where the costs of building are so high and the process is so drawn out (which creates additional and unnecessary financial risk for investors). There is no willingness to grapple with the fact that if costs — personal, political, and literal — were lower, it would make more sense to build a diversity of housing. Low- and middle-income housing gets built in other places, which suggests that we should compare San Francisco’s policies to those municipalities’ rather than claim that we're a unique snowflake dealing with unprecedented problems. The only thing unprecedented about our problems is our unwillingness to rationally respond to them.

(6) Incorrect claim 3: This is all the demand side’s fault

Many claim that tech is evil, foreign investors are evil, pieds-a-terre are evil, and Airbnbs are evil. It's all too simplistic. The forces behind those aren't singular movements or collectively one movement alone. They're the practical results of individuals making decisions that make sense to them. By making them singular it creates a simple enemy, but even if Ron Conway dropped dead, we'd still have a housing crisis. Even if Airbnb stopped operating, we'd still have a housing crisis.

(By the way, AirBnB was invented in 2007, and there was definitely a housing cost problem then too. That’s why it was founded. Airbnb can’t explain trends that old. Either way, most Airbnb hosts are not landlords systematically renting apartments on their platform — I've never seen that although I'm sure it exists — but rather individuals who cannot afford to live here without renting a bedroom out. I have friends who are an older couple who live in Eureka Valley, and the only way they are able to afford to retire is to rent out a bedroom that used to be occupied by one of their now-grown children.)

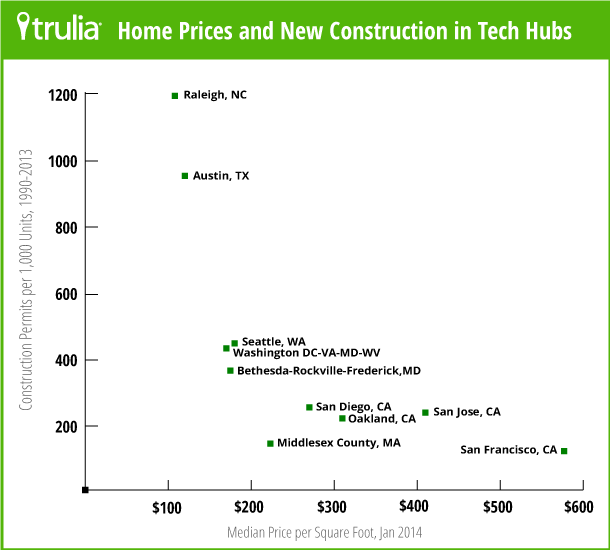

There is a direct relationship between the amount of building and the cost of housing. The following graph from Trulia perfectly illuminates that fact:

Here is the accompanying commentary:

San Francisco’s high home prices are extreme – but so is the lack of construction. Since 1990, there have been just 117 new housing units permitted per 1,000 housing units that existed in 1990 in San Francisco. That’s the lowest of the 10 tech hubs and among the lowest of all the 100 largest metros (see table 3), even with the recent San Francisco construction boom. Relative to San Francisco, Raleigh and Austin have ten and eight times as much construction, respectively. Geography limits construction in the Bay Area – it’s hard to build in the ocean, in the bay, or on steep hills – but regulations and development costs hurt, too.

(7) Incorrect policy solution: limit job growth

I have heard several folks say that we need to stop creating new jobs in San Francisco. The arrogant privilege required to say that we need to constrain job growth is startling. They should go to the Rust Belt and say that out loud and see what the reaction is to the sentiment. But that idea takes our revealed policy preferences to their logical conclusion. Every one hundred new jobs at Bay Area startups or technology companies are attracting more people here, which in turn raises prices, strains our public transit system, and displaces people. If the Bay Area is unwilling, as a matter of policy, to grow the housing stock and the transit capacity, do we have an ethical obligation to begin, as a matter of policy, slowing job and economic growth?

The first time I heard someone propose the idea, though, something switched in my head. I had been thinking about housing as a combination of social justice and of local economic implication: San Francisco and the Bay Area won't reach their highest moral or economic potential because of urban policy. But it's far bigger than that: the foolishness we exhibit locally means that California and the United States won't reach their economic potential — due to "Silicon Valley's" outsized role in state and federal economic growth and innovation.

We have been unwilling to deal with the consequences of our economic growth. Year-after-year, neighborhood-after-neighborhood, we are unwilling to invest in the housing, transportation, or infrastructure necessary to support the population growth that results from our positive economic growth. What’s more, we should be embracing and harnessing this job growth and influx of capital investment to create a housing policy that achieves the oft-stated goal of housing for

all.

(8) NYC example: harnessing market force to increase the affordable housing supply

We need to build much more housing immediately. We need to do that so that we can have a diverse city: ethnically and socioeconomically. If we choose to kill new housing in the face of the demand, we choose to destroy neighborhoods rather than adapt them. We choose a certain Victorian aesthetic, one that is only owned by the rich homeowners, over a truly multifaceted city.

We need to understand the true forces in the market (and the true financial constraints therein) and harness the market to build a large amount of diverse housing.

San Francisco’s policies are out-of-line with building almost anywhere else. For example, nowhere in San Francisco do you get density bonuses for affordability (like in New York City) and nowhere in San Francisco can you build as of right (like in almost every other municipality). And, perhaps most importantly, no where else is there a belief that you can solve a housing affordability crisis without encouraging the building of more housing.

I believe in inclusionary housing. New York City's recent sweeping housing policy changes have been cited in many recent housing conversations I have been in. But the flip side of that inclusionary bargain everywhere else in the world, and especially NYC, is more units, more density, and more housing. The AP article on the NYC change last week starts the way: "Many of New York City's residential neighborhoods will feature denser and taller development as part of a sweeping housing plan that will mandate the construction of more affordable housing and rewrite the city's decades-old zoning to enable more residential development" (emphasis added).

New York City’s new inclusionary housing policies are amazingly progressive, and I understand the simple desire to look at them and say that we could institute similar mandatory requirements. But the program in NYC only applies when a development needs a land use action (some type of variance to existing zoning)[7]. In New York City, and most other jurisdictions, if your proposed projects meets the zoning requirements, the approval is an administrative process: the public policy has already been described, debated, and decided in the zoning process. That is, most development in New York City occurs as-of-right. Developers can still build without these mandatory requirements, and, either way “In exchange [for the affordable housing increases], developers can be allowed to build taller structures and obtain low-interest financing and tax advantages.”

A 20% inclusionary requirement, or whatever that number should be, of every new building should include a diverse set of affordable housing for low and moderate incomes (teachers, public servants, service sector workers, the list goes on). But, with this requirement, the only thing that matters is how much total housing gets built. If it's 33% inclusionary and that means projects are upside down on their economics, then nothing gets built. Or, zero affordable units.

We need to set the inclusionary requirement at a rate that makes economic sense and, again, focuses on the only thing that matters: the total number of units that needs to get built. For example, the controller's recent report around Prop C says that increasing the inclusionary percentage to 25% will cause a 13% decrease in overall production. That is a backwards policy.

Why do we need to harness the market? Because housing is expensive to create. Even if we suddenly agreed to build all the affordable housing we need in the city — which we won't because not enough neighborhoods would accept that new housing — we can't build it all from public money. That money just doesn't exist. But capital investment does.

(9) Ten policy ideas to increase the supply of housing in San Francisco

Generally, I would approach this problem by setting an aggressive target for new building and then design incentives or eliminate restrictions to reach that goal.[8]

Let me quickly mention ten ideas that would have an positive impact on housing in the city:

Zone for more housing across the entire city. The city needs to upzone in terms of both density and heights in many parts of the city, particularly along transit corridors.[9] This upzoning should be targeted to specific blocks and lots within communities, but not just in underdeveloped (which is often code for poor and minorities) neighborhoods. There need to be denser, larger buildings in Pacific Heights and Presidio Heights, too.

Allow as-of-right building. We should have the same in San Francisco: which would reduce the costs of building and the time-to-market when a developer is building within the existing zoning requirements. Beyond this, we should also simplify and shorten the variance process. That doesn’t mean eliminating democracy (quite the opposite) but it does mean creating one-unified coherent set of policies and associated timelines (like NYC’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP)).

Reexamine bulk, parking, setback, and backyard requirements to encourage more density. For example, require much less parking, encouraging that space and money to be used for housing while also investing much more in public transit.

Continue a high, economically sustainable, inclusionary requirement for affordable housing. Affordable housing is absolutely critical and the best way to get more affordable housing is through a combination of a reasonable requirement coupled with as much building as possible. With this approach, we could easily double or triple the number of below market rate (BMR) units in the city within a decade. If we prevent building, the number might scarcely increase at all.

Increase investment in public housing by renovating and preserving the units, building more public housing in neighborhoods across the city, and set aside money when the economy is good to build public housing when the economy is bad.

Allow for smaller more affordable units to be built, what SPUR calls “Affordable by Design.”

Allow for an increase in the legalization of in-law and secondary units (even if they are going to be used for Airbnb - better these spaces be used than larger, higher occupancy ones).

Rezone underutilized industrial and commercial zoning to housing.

Create incentives for replacing underutilized sites throughout the city, including upzoning and a simplified permitting procedure.

Consider big ideas that have worked elsewhere. For example, developing a Mitchell-Lama Housing-like program by building public-private partnerships so more housing can be built. That program had a ton of flaws and would need to be significantly reworked, but you couldn’t fault it for a lack of ambition.

I would also like to consider larger, bolder solutions that haven’t been tried yet. Maybe there is a grand bargain between the “sides” or maybe the pro-housing side just needs to win a political victory. Either way, we need a grand bargain that builds much more housing — over 100,000 units are needed by some estimates — in San Francisco, with a large chunk of it being affordable.

Everything should be on the table to make that happen. Our city, and the livelihood of many of our fellow citizens, depends on it. Right now, the future is bleak and only because of our own choices. Let’s make a promise — to each other and to the future generations of San Franciscans — to execute on a housing policy that preserves the spirit of this city. That’s a promise worth keeping.

Endnotes

[0] Census Bureau Estimates of San Francisco County’s population over the last three years:

2013: 840,715

2014: 852,537

2015: 864,816

So, in each of the last two years, San Francisco’s population grew by approximately 12,000 people. The city’s housing stock has increased by approximately the same amount -- 24,000 units at least according to Scott Weiner’s blog post cited below -- since 2003. That’s with over 100,000 people moving to the city since 2003.

[1] This blog post is born from an event last Wednesday evening (March 23). I organized a panel called “Affordable Housing - What's the Right Answer?” at the Eureka Valley Neighborhood Association, of which I’m on the board. The idea behind the panel was to have a selection of perspectives within the entire spectrum of perspectives on housing in San Francisco. The panel guests were Peter Cohen from the Council of Community Housing Organizations and Dennis Richards from the San Francisco Planning Commission. We had invited Tim Colen from the San Francisco Housing Action Coalition, to have a wider range of perspectives, but he was unable to attend at the last minute.

I left the panel energized but only because I disagree with both of the panelists that came. I wish that Tim was there. It it might have been less civil but it might have been more constructive. Overall, I ended up finding the conversation quite frustrating. I did my absolute best to keep my perspective to myself — I didn't talk very much — and just asked questions. But after the meeting, I couldn't contain myself and sent a long rant to the EVNA board. This post is an edited version of that email.

[2] Many sources have influenced my overall thinking about housing. Starting with my time working with and around city governments (particularly New York City, and also Newark, NJ) but also a ton of great reading out there, like, my Supervisor Scott Weiner on how "Yes, Supply & Demand Apply to Housing, Even in San Francisco", SPUR President Gabe Metcalf's writings, including, "What's the Matter With San Francisco?", subtitled “The city’s devastating affordability crisis has an unlikely villain—its famed progressive politics", or, of course, Kim-Mai Cutler's well-known posts on the history and realities of housing in San Francisco and California, for example, "How Burrowing Owls Lead To Vomiting Anarchists (Or SF’s Housing Crisis Explained)".

[3] Planning Commissioner Dennis Richard claimed this fact last Wednesday night on the panel: that we don’t need a single new unit of housing built in the city. I just cannot believe it. Peter could not believe that claim either, and that's saying something!

[4] This is a favorite argument of Peter Cohen that just sounds so sweet, but...

[5] Even I’ve written about big banks needing to be punished, but finance or financial services companies aren’t monolithically good or bad. They’re complicated. They’re different. Many investors are pension funds or university endowments.

[6] I recommend this amazing recent book on the financial crisis for a good rendition of monetary system design in this regard.

[7] Things are a little more complicated than I’m saying, but not much. “Land use actions” include both “private rezonings”, which are variances for individual projects and, I believe, the more important point here. “City neighborhood plans” also must include mandatory affordability, but those don’t happen particularly frequently.

[8] One thing that I do agree with housing advocates around is preventing speculation on real estate: policy should discourage it and encourage inexpensive housing. This post is about building a lot more housing, though, not discouraging housing speculation.

[9] Density is an under appreciated constraint on housing: density limits based on lot area encourage very large units.